“In my Community, a girl like me is rare”

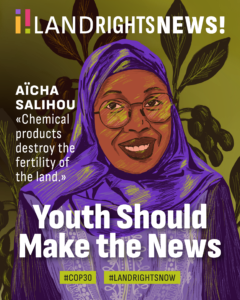

Aïcha Salihou on Climate Justice and Women’s Land Rights in Northern Cameroon

“In my community, female education is like a taboo. I am the most educated girl in my community.”

At 27, Aïcha Salihou is many things at once. She serves as the Secretary General of the Mbororo Social and Cultural Development Association (MBOSCUDA), a member of the International Land Coalition (ILC), and is dedicated to implementing restoration projects such as agroforestry to combat land degradation. She is also a social and climate activist, a law student, and a youth leader in northern Cameroon. Aïcha is a proud member of the Mbororo people, an Indigenous pastoralist community spread across several regions of the country.

From a place where girls are rarely allowed to go to school and women are largely excluded from decisions, Aïcha is working to restore not only degraded land, but also dignity, rights, and possibilities for Mbororo women.

Cameroon landscape

My country, Cameroon, is divided into two parts, the southern part is covered with grass and trees. The northern part, where I am living, is facing climate change challenges.

In the north region, where Aïcha lives, the land is dry and degraded. Trees have been cut down for firewood and other uses, grasses have disappeared, and the soil has lost its fertility.

“There are no trees, there are no grasses, so we are suffering from that. We raise cattle and other animals, but there is nothing for them to eat. The land is degraded.”

Here, climate change is not an abstract concept. It is extreme heat, short and unreliable rainy seasons, flooding during heavy rains, and dry, exhausted soil that can no longer feed people or animals.

A Young Woman Leading Restoration in a Patriarchal Context

In this harsh context, Aïcha has chosen to lead restoration projects as a young woman in a deeply patriarchal society.

In the north region, women are not considered,” she says. “They are not part of decision-making pro

cesses. It’s as if they don’t have importance.

Rather than accepting this, she decided to make women central to climate solutions.

As an ILC Fellow (2023–2024 cohort), she was invited to design a six-month project. Her response was a project t

hat combines climate resilience, economic empowerment, and women’s rights: “Empowering Mbororo Women of the North Region of Cameroon through the Practice of Agroforestry”

Agroforestry: Trees, Crops, Animals – and women at the centre

For her fellowship project, Aïcha chose agroforestry as a tool to heal both land and livelihoods.

“Agroforestry is when we have agriculture, planting of trees, and breeding together,” she explains.

Working mainly with women and young girls from Mbororo communities, she and her team:

- Planted many species of trees to restore degraded soils and bring back shade and moisture.

- Introduced soya beans, a crop recommended by agronomists for its ability to restore soil fertility.

- Supported the breeding of small ruminants, such as goats and sheep, so that women could improve their income and use manure to enrich the soil.

She also encouraged a simple but powerful technique: rotation of farming.

“If we have a piece of land divided into two parts,” Aïcha explains, “the first part is for agriculture and the second for rearing animals. The next year, we rotate. Where we did agriculture, we rear cattle; where we reared cattle, we plant crops. The residues of animals are very fertile for the soil.”

Through these practices, Aïcha helps communities adapt to climate change, but she is also doing something more subtle: she is creating space for Mbororo women to lead.

“They don’t know they have rights over land”

The Mbororo are an Indigenous minority officially recognized by the United Nations. In Cameroon, they live in several regions – Northwest, Southwest, East, and the Northern region – and are traditionally pastoralists, living from cattle rearing and agriculture.

In the north, where Aïcha comes from, many Mbororo communities are unaware of their land rights.

“Most of us just know cattle rearing and agriculture,” she says. “Mbororo women don’t know they have rights over land.”

In her community, a woman can only access land through a man, being her husband, her son, or her brother.

For Mbororo women to get access to land in Cameroon, it is basically through a man,” Aïcha explains. “Mbororo women are considered dependent. They depend on their families, mostly on their husbands. It is difficult for them to afford everything they want.

This dependency not only affects their daily lives but also limits their capacity to respond to the climate crisis that is transforming their territory.

Indigenous people are the ones living from the land and on the land,” she says. “They should normally have solutions to climate change because they are closer to the environment. But since they lack education and sensitization, they suffer from its effects.

From Land Grabs to Law School: A Personal Turning Point

Aïcha’s activism is deeply rooted in her own story.

In my community, I am the most educated girl. Female education is very rare. At first, it was like a taboo to send girls to school.

She watched as her parents and elders lost land to administrators and powerful actors simply because they did not know their rights.

“Administrators and others were taking their lands because they are ignorant,” she recalls. “That pushed me to study law – to know the rules and regulations, our obligations and our rights, especially our land rights.”

Today, her legal education and field experience feed directly into her activism. Through sensitization campaigns, she explains:

- what land rights are,

- why women also have rights, and

- how communities can protect themselves from exploitation.

At the same time, she promotes practical climate solutions: planting trees, avoiding chemical fertilizers, using natural products, and stopping harmful practices like cutting down entire trees or setting bushfires for hunting or honey collection.

Who Is Degrading the Land?

When asked who is putting the land in danger, Aïcha doesn’t point to a single villain.

“I can say farmers and industries. All of them are responsible for land degradation – maybe out of ignorance, because they don’t know the consequences.”

She lists multiple causes:

- Industrial activities using chemical products that pollute soil and air.

- Agriculture on the same land for too long without restoring fertility.

- Deforestation – cutting down entire trees for fuel instead of pruning branches.

- Bushfires for hunting and honey, which destroy vegetation.

- Flooding during heavy rains on already degraded land.

- Lack of knowledge about sustainable agricultural practices.

Her work is not about blaming communities, but about building awareness and alternatives.

Youth and women’s voice for COP and Beyond

Some of Aïcha’s colleagues were able to attend global spaces such as the COP climate conferences, and she has a clear message for these processes:

“Youths should equally be implicated,” she insists. “It should not be only those who are used to going there. It should be an opportunity for everybody – every competent person – to go, to see, and to express themselves.”

For her, youth and women must be present not just as symbols, but as real decision-makers:

Most of the time, women are not participating, and youths are not seen. If youths could be more implicated so that their voices and their cries are taken into consideration, it would be very interesting.

Her wish is simple and powerful:

“That my voice will be heard, and that I should contribute to the development of my community.”

From a dry, deforested corner of northern Cameroon, Aïcha Salihou is proving that climate justice is not only about restoring land – it is also about restoring voices, especially those of young Indigenous women who have been told for too long that they do not belong in the conversation.