“Without Secure Land Rights, There Is No Real Climate Justice”

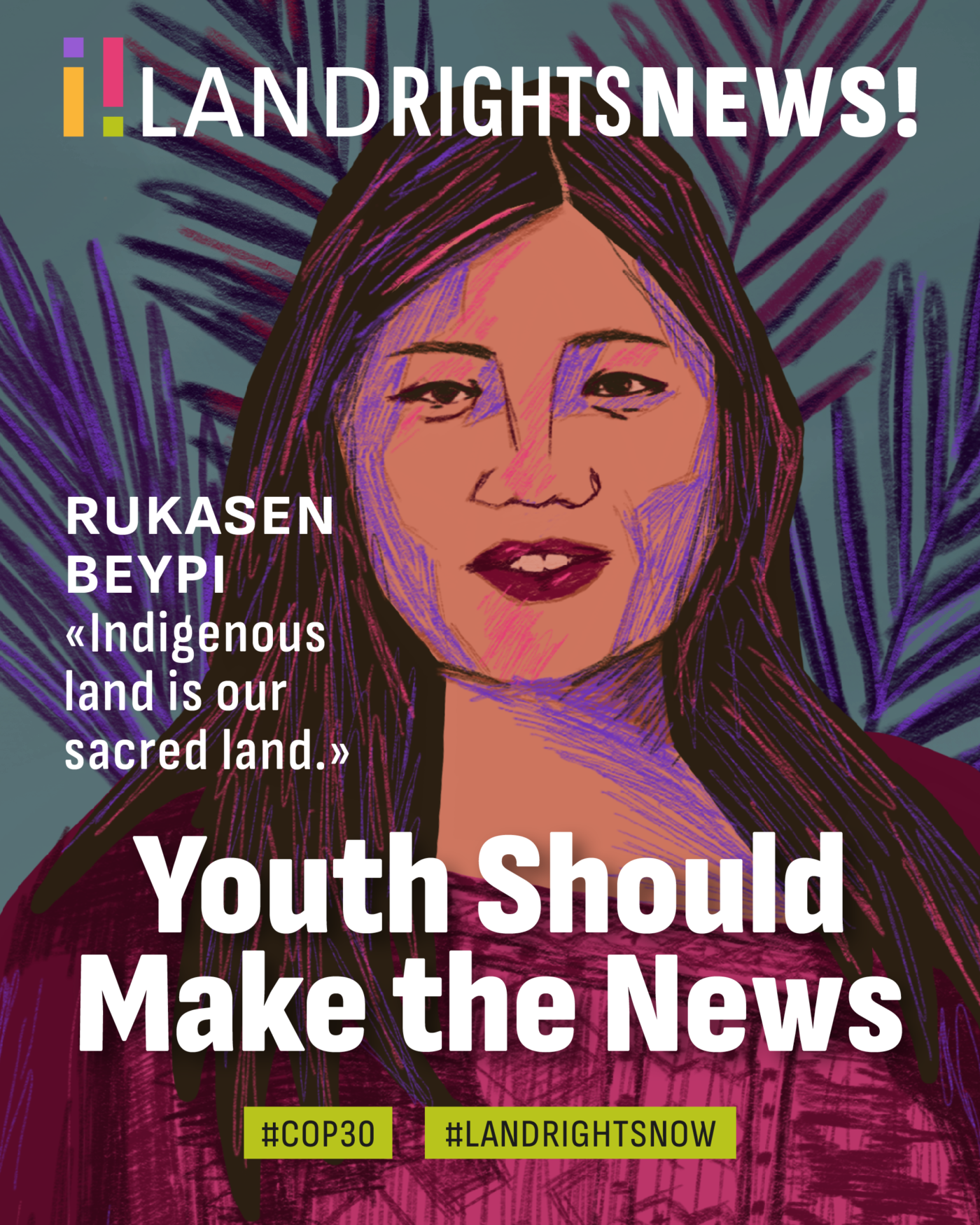

Rukasen Beypi

“For us, the land is not just resources. When we talk about Indigenous land, it is our sacred land, our territory, our identity – and our life.”

At 31, Rukasen Beypi is part of a new generation of Indigenous leaders connecting village struggles in Northeast India to global climate debates.

Rukasen comes from the Karbi community in Karbi Anglong, a hilly district in the state of Assam, in Northeast India. They work as a fellow with AIPP – the Asia Indigenous Peoples Foundation, a regional human rights organization based in Chiang Mai, Thailand, and have been active in Indigenous youth advocacy and human rights since 2016.

Through AIPP and its Asia Indigenous Youth Platform, where Rukasen served as Deputy Chair for three years, she helps building regional networks, support grassroots organizing, and strengthen the leadership of Indigenous youth across Asia.

Land as sacred territory

Rukasen’s homeland, Karbi Anglong, is often described in simple geographic terms: a “Scheduled Tribes Hills” area of Assam, rich in forests, rivers, and biodiversity.

But for the Karbi people, the land is much more than that.

“It’s a beautiful, hilly region, but when we talk about Indigenous land, it’s our sacred land, our territory, our identity, and also our life.”

This perspective is at the core of their activism. Land is not a commodity; it is the foundation of their culture, expressed through stories, rituals, and songs. It shapes their language, which is rooted in place, and carries their traditional knowledge about forests, water, seasons, and healing. It also sustains their livelihoods through small-scale farming, forest gathering, and shifting cultivation.

When land is taken, it’s not just an economic loss. It is a rupture in the fabric of life.

Forests under attack: Deforestation, mining and palm oil

Today, a large share of Karbi Anglong’s forests is under threat.

“A large part of our forests is being lost due to deforestation,” Rukasen explains. “Like other Indigenous lands, we also face mining and unplanned development.”

On top of that, the Indian government is planning large-scale palm oil plantations in Assam, including Indigenous forest areas.

We have learned from Southeast Asia what happens with palm oil, now our government wants to take away Indigenous forest land in Assam for palm oil plantations.

The lessons from Indonesia, Malaysia and other countries are clear: massive deforestation, loss of biodiversity, polluted rivers and soil, and communities are displaced or pushed into wage labor on their own land. For Karbi communities, this is not an abstract “risk” – it’s a real, looming threat.

Land grabbing and forced migration

The community also faces land grabbing, both by companies and by more powerful social groups.

“We face land grabbing not only from outside actors, but also from high-caste people in Assam,” Rukasen notes.

Traditional livelihoods like small-scale farming and forest-based activities are becoming less secure. Young people often feel they have no choice but to leave.

“Young people are forced to migrate because their traditional livelihoods are no longer secure like before,” explains.

Migration might bring short-term income, but it also weakens community cohesion, pulls youth away from their language and culture, and makes it harder to defend the territory because fewer young people remain to carry on the struggle.

Climate change: rains at the wrong time, crops failing

Climate change is intensifying all these pressures, as many community members explain when they say that the rains now come at the wrong time, crops fail, and challenges appear that they had never faced before. Traditional planting calendars no longer work, farmers lose harvests they once relied on, and food insecurity grows. With each difficult year, the shock pushes more people into debt, migration, or dependence on external markets.

None of this affects only the economy. As Rukasen stresses, nature and culture are inseparable:

“This puts not just nature, but also our culture, language, and traditional knowledge at risk.”

When forests disappear, songs and stories tied to them begin to fade as well.

AIPP work and why youth networks matter

Through their work with AIPP, Rukasen helps connect these local realities to regional and global advocacy.

AIPP focuses on five key program areas:

- Human rights

- Environment and climate

- Land, territories and resources

- Regional capacity building for youth and communities

- Organizational strengthening, so Indigenous organizations can sustain their work

Rukasen has also been deeply involved in the Asia Indigenous Youth Platform, a network of young Indigenous activists from across Asia.

“We work on regional capacity-building for youth. It’s about strengthening our voices and sharing strategies across countries.”

In other words: building collective power, so that communities facing palm oil in India can learn from those who already faced it in Southeast Asia—and so youth are not isolated in their struggles.

“Our Stories Matter”

Asked what she is demanding from global spaces like COP30, Rukasen is clear and concise.

First: the world must listen to frontline communities.

Our stories matter, the world needs to hear the voices of those most affected by the climate crisis.

For Rukasen, this also means transforming the role of media:

Media should amplify grassroots stories, not just negotiations. They should show how communities are adapting and leading solutions.

Media should amplify grassroots stories, not just negotiations. They should show how communities are adapting and leading solutions.

Second: recognition and protection of Indigenous territories.

“We always demand legal recognition and protection of Indigenous territories and resources, without secure land rights, our communities remain vulnerable to exploitation, displacement, and climate impacts.”

For her, land rights are not a side issue; they are a precondition for real climate justice:

“Recognising territorial rights is essential for real climate justice.”

Finally, Rukasen insists on meaningful participation for Indigenous youth. COPs and climate events increasingly feature youth panels and Indigenous pavilions – but too often, young people are invited to be seen, not truly heard.

“They say this time it’s an Indigenous pavilion, but there should be meaningful participation of Indigenous youth as well.”

For Rukasen, this means ensuring that youth are genuinely included in decision-making processes and not confined to side events or symbolic spaces. It means treating youth as true partners rather than just “participants,” and it calls for an end to tokenistic practices in which a select few are highlighted while real power structures remain unchanged.

“Indigenous youth should not be taken as tokenism. We need meaningful spaces in decision-making processes – not just as participants, but as partners.”

Learn more about Rukasen’s regional work through AIPP at: aippnet.org