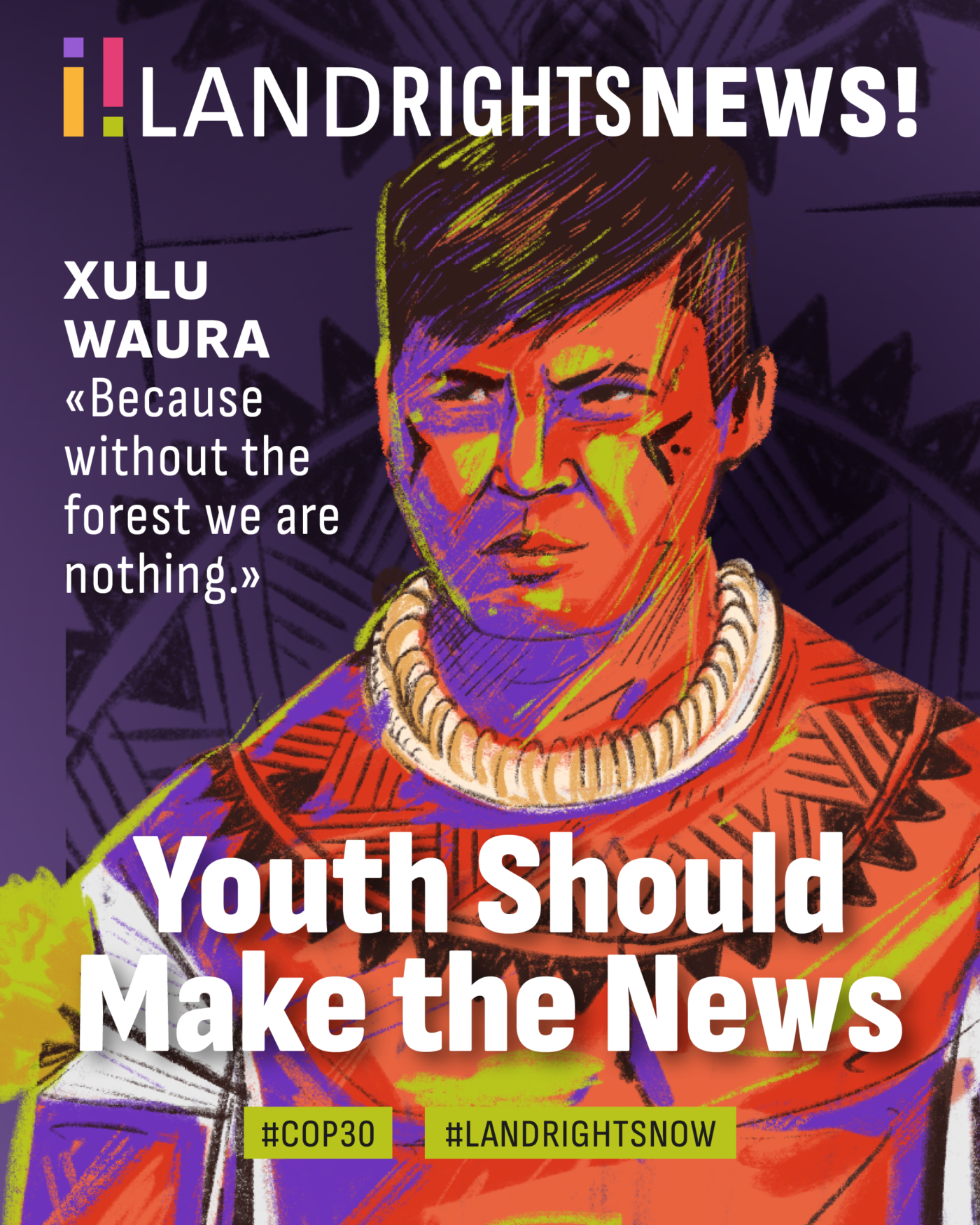

Xulu waura

“Without the forest, we are nothing” – Xulu Waura on Kamukuwaka, climate change and youth resistance in the Xingu

“In 2015 it was still fresh. Today it’s too hot. Our houses can’t hold the sun anymore. Children’s skin are breaking out in rashes. The climate is making us sick.”

At 25, Xulu Waura is part of a generation that inherited both a territory and a struggle. He is from the Waura people in Mato Grosso, Brazil, and lives in the Upper Xingu, within the Indigenous Territory of the Xingu. Xulu serves as Secretary of the Youth Movement of the Xingu Territory (MJTIX) and organizes alongside other young people to defend their land, culture and future. His activism is rooted in a powerful family legacy – and in a sacred cave that now lies outside his people’s officially recognized land.

“My grandfather demarcated the land – but the cave was left out”

Xulu describes his story as an inheritance of struggle. “I come from a legacy of resistance. My grandfather, Atamai Waura, was one of the warriors, one of the leaders who demarcated our territory.” In 1995, his grandfather and other leaders fought for and secured the demarcation of the Wauja people’s territory. But there was a painful omission. Because he didn’t speak Portuguese well and depended on outside experts to translate and write reports, the cave of Kamukuwaka – a site central to Waura culture – was left outside the demarcated Indigenous land.

The anthropologists helped him, but they only included half of what should be ours. They didn’t include the cave called Kamukuwaka. That cave is the one that created the songs, the stories, the speech, the painting, the rules of my people.

Kamukuwaka ended up about 45 km outside the recognized territory.

In 2002, they tried again, initiating a process to formally recognize the cave area. But, as Xulu explains, his grandfather misunderstood the legal language. “He thought ‘homologation’ meant a new demarcation, that it would bring more respect. He didn’t understand that it was only a recognition of that small area, not a full protection like the territory.” The result was that the cave area was homologated, but not integrated into the wider Indigenous territory.

This legal gap opened space for outsiders, farmers, miners to enter and plunder.

“People started going there and taking things. There was a stone fish, a surubim. When you touched it, it turned to stone; when you walked away, it would move again. People said it was beautiful. Today it’s gone. They stole it to sell, not even in Brazil, but to other countries, like Switzerland.”

For Xulu, the story of Kamukuwaka is not only about theft of sacred objects; it is about how colonial laws continue to separate people from the heart of their culture.

The sacred cave of Kamukuwaka

When Xulu speaks of Kamukuwaka, he uses the language of reverence. “Kamukuwaka is like a god for us. He is a creator.” In Wauja cosmology, Kamukuwaka is the being who created the songs (cantoria), gave the body painting patterns, established rules of living – such as how to treat animals and what can or cannot be eaten – and taught what is right and what is wrong.

Inside the cave, Xulu says, there are traces of this creator.

In that cave there are his things – manioc flour, a fish trap – all turned to stone. It is very important for the next generations to know that place, so they don’t forget their culture and their identity.” Many young people, however, have never been there. “There are generations who don’t know who they are. If you ask some of them, ‘Who are you? What is your origin?’ they won’t know, because no one took them to that cave to understand where our people come from.

For Xulu, defending Kamukuwaka is defending memory, identity and a spiritual geography that holds together the Wauja world.

Life in the Upper Xingu

Xulu lives in the Upper Xingu region, where nine different Indigenous peoples share a landscape and related cultural practices. But climate change and industrial pressure are transforming this territory. “We are suffering with climate change – fires, logging, and the river drying up.”

The main food staple, manioc (cassava), is no longer reliable. “We plant manioc, but it doesn’t grow because it’s too hot. Every year we lose the crops.

We have to search in other communities or even buy seedlings in town to plant again. Because of this, we are going hungry.” The community’s diet is traditionally based on hunting, fishing and forest plants, not on proce

ssed food from the city. “We don’t survive well on the white people’s merchandise. We can eat it sometimes, but it’s not good for our health. We prefer traditional food.”

Since around 2020, the situation has deteriorated quickly. River levels have dropped dramatically, fish are dying, and many animals are succumbing to agrotoxins. Although the Indigenous communities do not use pesticides, they are surrounded by agribusiness.

On the border of our territory there are farms. The river’s channel passes through these farms. Even though we don’t use agrotoxins, they arrive through the river. We can’t stop them – that land is legally theirs. We can only watch. That is what is impacting our territory. Sometimes we don’t have native animals to use in our rituals and songs. This affects our culture, not only our food.

“We don’t live with air conditioning”

When Xulu travelled to COP30 in Belém, he carried a clear message: Indigenous youth must have a space where governments truly listen.

My demand for COP is that Indigenous youth have a space where governments listen to us. We are the ones suffering in the territory. We don’t live with air conditioning. We live naturally. We are not prepared for this heat.

His proposal is simple yet powerful: “We need Indigenous representatives at COP to speak for all of us, to fight for us, and to be truly heard. We want COP to bring results for us – what our grandparents asked for, what we have been demanding for years. Now the grandchildren have grown and are continuing their struggle.”

Asked what his community and its neighbours can teach the world about climate, Xulu doesn’t hesitate. “We can teach people to see how much nature is worth.” He points to reforestation as a concrete example. In an area that had lost its trees, the community led a local restoration effort. “There was an area that used to dry out. It had no forest. We reforested it, especially with pequi trees. It helped a lot. In that region, the streams stopped drying up.”

For him, the lesson is straightforward: if everyone reforested areas that have lost their forest cover, climate change could be significantly mitigated.

Three biggest threats to the Xingu territory

When asked to identify the three main threats to their territory, Xulu lists illegal logging, fires and sport fishing. Illegal logging is particularly devastating because it includes species used as traditional medicine. “There is a type of wood we use as medicine. It no longer exists in some areas because they are removing it.”

Fires, both intentional and natural, have intensified with drought and rising temperatures. Sport fishing, though often branded as “catch and release”, also harms the ecosystem. “They catch the fish and release them, and say ‘We’re not killing them.’ But some days later, that fish dies. It’s not good.”

These pressures converge on the same victim: the forest that sustains Waura culture, health and education.

“Culture, health and education are in the forest”

To close, Xulu insists on something he wants outsiders to truly understand. “Our culture is in the forest. Our health is in the forest. Our education is in the forest.” When someone gets sick, he explains, pharmaceutical medicines often do not work as well as medicinal plants. “Without the herbs, we can’t survive.”

And without trees, there is no material for building houses (ocas), making ritual objects, or preparing ceremonies and songs. “Without the forest, we will no longer have culture. We won’t be able to perform rituals, to build houses, to continue being who we are. There are many things in the forest that are important for us as Indigenous peoples.”

From the Upper Xingu, from a territory where rivers run alongside soybean fields and lightning ignites dried-out forest, Xulu speaks as part of a generation that refuses to give up. They are reforesting, organizing and carrying forward the fight of their grandparents – for Kamukuwaka, for the Xingu and for a future in which the forest is finally valued more than profit.

You can find Xulu on Instagram at @xulu_wr and follow the Youth Movement of the Xingu Territory (MJTIX) at @mj_tix.