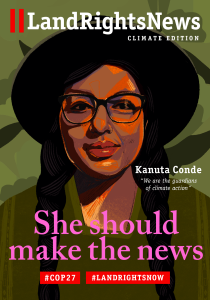

For Aymara woman and Youth Climate Activist Kantuta Conde, the path to climate justice begins with reciprocity. Whereas the concept of “sustainable development” has been popularized in international climate discourses during the last three centuries, her people have been living sustainably with the land for generations. In Kantuta’s words, “the forest is a being onto itself. It is life itself. It is our life.”

At only twenty-one years old, Kantuta’s seasoned work in activism belies her age. Her path in advocacy began during her childhood, when she assisted her parents in the reconstitution of the ayllus, a practice to recognize and reclaim the ancestral Aymara territory. Her own name, Kantuta, a traditional Bolivian flower and Aymara princess, connects her to her identity: “I inherit from this history, from this rituality”. Listening and recording the assemblies inspired her to advocate for her people’s rights and sovereignty at the national and international level.

As a current member of the regional organization Red de Jóvenes Indígenas, Kantuta’s work combines themes of Indigenous political participation, care for the earth, health, and cultural revitalization in her approach to climate justice. Her interdisciplinary involvement is reflected in the diversity of her organizational affiliations, including the International Land Coalition, UNICEF’s Voices of Youth platform, the Pan American Health Organization’s Youth Caucus, as a participating member at the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, and as a law student in the Universidad Mayor de San Andres.

Yet when asked about her extensive resume, Kantuta remains true to her humble nature. At the center of her work, she says, is “the theme of responsibility.” Indigenous youth, she believes, are responsible for promoting intergenerational dialogues, which have been used for millenia to teach young Aymara about community and territorial stewardship. In the era of COVID-19, the use of traditional Aymara medicines and health practices has foregrounded the importance of the land as a source of mental, physical, and spiritual health. As they care for the land, so does the land provide the resources to care for their community.

Climate change threatens the balanced relationships that define traditional Aymara ontologies of land. A report published by Oxfam in 2020 predicted that the fragile ecosystem of the Bolivian Altiplano is particularly vulnerable to extreme drought; a phenomenon that will exacerbate poverty, food insecurity, and inequality in a country where Indigenous communities already face marginalization.[mfn] Painter, James. “Climate Change, Inequality and Resilience in Bolivia.” Policy Papers. Oxfam International, December 3, 2020. https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/climate-change-inequality-and-resilience-bolivia. [/mfn] A secondary effect of these ecological changes are shifting patterns of extraction and migration; developments which Kantuta notes have already begun to impact her community.

“The forced displacement” Kantuta explains, is traumatic in ways beyond the physical effects it renders to the Aymara. Rather, it is also a mental health crisis which “is also the experience of disconnection from our identity, and a disconnection from the spirituality of the land.” It is for this reason that, despite the dangers of climate activism, Kantuta feels she and other Indigeous youth activists have little choice but to continue fighting for climate justice and Indigenous territorial rights.[mfn]“A Deadly Decade for Land and Environmental Activists – with a Killing Every Two Days.” Land and Environmental Defenders. Global Witness, September 29, 2022. https://www.globalwitness.org/en/press-releases/deadly-decade-land-and-environmental-activists-killing-every-two-days/. [/mfn] “The defense of the territory is very dangerous,” Conde admits, “It is much easier to let it go. However, we cannot. It is necessary to continue on this path.”

Ahead of COP27, Kantuta hopes that the experiences and traditional knowledge possessed by Indigenous youth can serve as a guide for world leaders seeking to confront the climate conference. Indigeous youth, she says, can teach the rest of the world to view the impacts of climate change intersectionality, as her community experiences them.

“I cannot speak about climate change without talking about our land and territory, traditional knowledge, indigenous languages and mental health, everything is interconnected.”

To effectively incorporate Indigenous youth leadership into global climate discourses, Kantuta believes strongly that steps to increase the accessibility of the COP must be taken. The ubiquity of discourses in English preclude many Indigenous youth from participating fully in international summits and policymaking. The effects of this could be mitigated, Kantuta says, if written materials and presentations were made available in multiple regional languages; an accessibility measure that was conspicuously absent at last year’s COP26 in Glasgow. Further, she wishes to see fellowships made available to Indigenous youth climate activists by the UNFCCC to increase the scientific knowledge of climate change, and strengthen their organizations. Finally, Kantuta asks for a cultural shift away from paradigms that position Indigenous people as the victims of climate change.

“Indigenous Peoples are not victims, she says. “Indigenous youths are guardians of climate action.”

Follow Kantuta and the other members of Red de Jovenes Indígenas on social media: Website, Twitter, Facebook,. You can also reach them by email at juventudindigenalac@gmail.com.